(This blog is based on a session at our Eighth Annual CEO Summit in Washington, DC with Michael Roberts, Professor of Finance with The Wharton School.)

“Cash is king”. This is by far the best summary of a broad swath of financial theory. Companies that generate a lot of cash, fast, and with little risk are very valuable. Companies whose cash flows are riskier or will take time to realize are less valuable. And then there is Uber.

Earlier this year, Uber had its IPO at a valuation of over $75 billion, putting it in the Top 100 of the S&P 500. The same quarter it had its IPO, Uber posted losses of $5.2 billion.

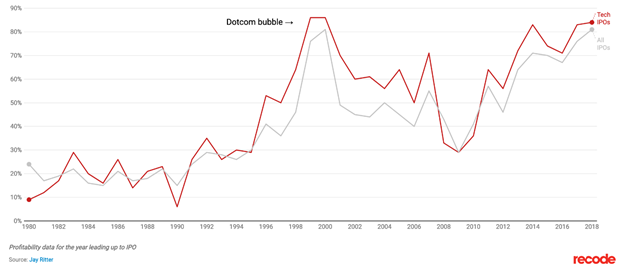

Share of US IPOs that are not profitable

As a growth equity firm, we are hardly the ones to point fingers. While we encourage companies in our portfolio to be capital-efficient, we do prioritize growth (it is in the name) and recognize that the majority of them will not see a cent of profits until our exit. But it is a gnawing question – if value is tied to profits, how do you reconcile the two?

To show this, let us draw on an example from a different era of exuberance – the late 1990s.

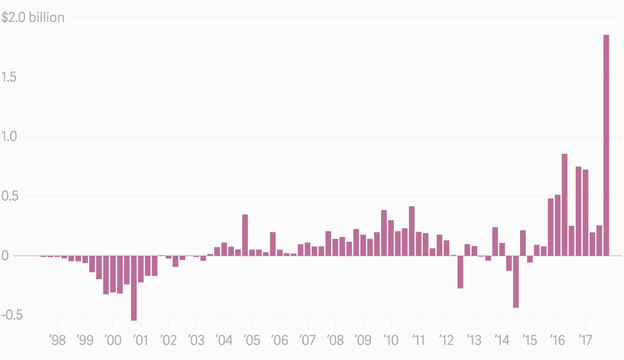

Amazon had its IPO just 22 years before Uber - on May 15, 1997 at an initial market cap of $438M. Not only was the company not profitable at the time, but it continued to burn increasingly more money, peaking with a quarterly loss of over $500M in the last quarter of 2000. The company did not break even until 2003, six years after its IPO.

AMZN Quarterly Net Income (US$billion)

So how was the valuation justified? To put it plainly, investors expected that the company will eventually generate enough free cash flow – so much, in fact, that, even when you discount it for time and risk, it will make this bet well worth it. In case you are curious, the company’s 2Q19 earnings were $8.3bn. They don’t fit on the chart above.

This brings us back to the conversation of what the expectation is for the unprofitable technology companies of today. The bet on a large payout in the future falls in several categories:

- Overcoming barriers to entry: based on the assumption that a market has very high fixed costs, investors bet on the company growing to a point where those costs are covered and it becomes profitable (e.g. it takes a lot of money to research a cancer drug, whether successful or not)

- Achieving economies of scale: encompassing the modern push for network effects, this is a bet that as the company grows its product becomes either more valuable or cheaper to deliver, pushing it into profitability (e.g., as more people join Slack, the value of joining Slack increases)

- Capturing a market: investors believe that the company operates in a winner-takes-all market, where it will be able to become a dominant player (Amazon controls nearly half of all ecommerce in the United States, and is beginning to face regulatory pressure for it)

If you are reading this, however, chances are that you are a growth-stage company that might not have an IPO in its sights. So does this still apply to you? Even if you are out to eventually be acquired, rather than go public, the same logic applies. An analyst somewhere, whether on a corp dev team or inside a bank, will try to figure out what your value is in cold, hard cash. And here are a few of the ways they would think about it:

- Ability to drive revenue: Will your product enhance the value of the existing one? Will they be able to sell more or charge more?

- Ability to reduce costs: Will you drive cost efficiencies in the joined organization?

- Contribution to long-term objectives: Will you help with overcoming the barriers to entry, achieving economies of scale, or capturing a market?

If the answer to at least some of these questions is yes, there is a direct path to you generating cash flows for the company that acquires you – even if you are not profitable today. If the answer is "no," you might want to look hard at the underlying business model and the profile of your potential acquirers.

At this point, you are likely getting ready to challenge the argument (and that’s great)! You may be thinking about cases where a company gets acquired for a crazy valuation just to prevent a competitor from buying them. Or where it is all about their brand. Or where they have no revenues to speak of, let alone profits. I will bet you, though, that at the bottom of each of those lies a strong (if risky or even wrong) cash flow analysis.

A special thank you to Carlo, the son of VP Finance Joe Giquinto, for allowing us to use a photo of him from our 2018 holiday video for this blog banner.