A fair share has been written recently about how the coveted unicorn status is over-hyped. If you, like me, start your day with Anand's CB Insights newsletter, you may have woken up to a well-curated exposé on the topic aptly titled "f*#k unicorns." To sum it all up, some people in the industry suggested that not achieving unicorn status equates with failure, and then others argued that blindly chasing a $1 billion vanity valuation can be distracting, delusional and dangerous.

For what it's worth, I generally side with the latter (admittedly with a dose of bias from seeing Edison's most successful portfolio companies exit at well below a billion dollars). On a normal day I would probably stop here and pen up a few quick sentences of agreement to join the rising chorus of investors who are (very) happy to underwrite exits in the hundreds of millions...

...but a restless, curious part of me wants to better understand how we got so obsessed with unicorn-chasing. To help me figure out what is going on I threw some data against the wall (in this case, mostly PitchBook's) and a few interesting things came out. Bear in mind that this is still a quick-and-dirty analysis and I probably missed a few obvious things, but the logic should still be directionally correct.

1) Unicorns are rare, but they matter

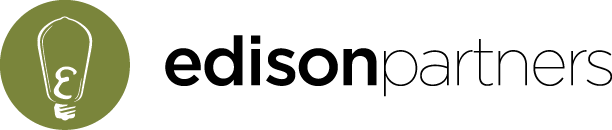

Below is the median valuation at exit of venture-backed software companies since 2007 (which should capture something close to a full economic cycle). I have thrown in the first and third quartiles, so you can get an idea of the spread.

The simple truth – over the last decade, the median tech company exited for $65 million. Even if you take the first quartile (capping out at a very respectable $290 million), that is still a long way away from the coveted $1 billion mark.

In fact, in the past decade, only 139 of 11,640 total exits held a valuation of over $1 billion. This means that even if you get to an exit (and that is no small feat), you still only have a 1.2% chance of being a unicorn. If you prefer a cohort-based analysis, you can check out CB Insights' numbers here (they reach a strikingly similar conclusion).

On the flip side, those 139 deals accounted for a cumulative $527 billion in enterprise value at the time of their exit/IPO. Just to put this in perspective, this is roughly equal to the combined market cap of Wal-Mart and Bank of America. The sheer scale of the economic impact generated, combined with the societal change resulting from the disruption they bring, is what makes unicorns very relevant (if rare).

2) Unicorns are (generally) great for investors

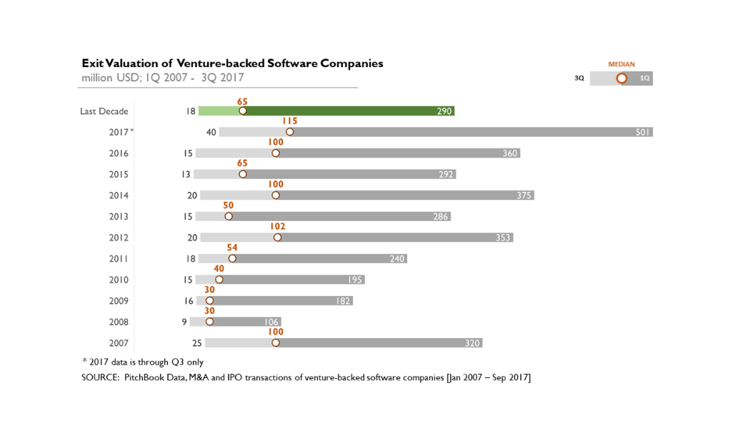

It is hard to tell who makes how much money on VC-backed exits, but for a fair share of outcomes, we can tell how much they raised overall and how much they sold for. The outcomes for founders and specific investors vary based on the cap table, but this is not a bad proxy for how well people did overall. Here is the data from 1750+ exits over the past decade:

Just to get the low range of outcomes out of the way, it is clear that it is very hard to make money on outcomes of less than $10 million, and it gets progressively easier as the valuation goes up to $100 million.

It is at this point where things gets interesting. Between $100 million and $1 billion of enterprise value, the median company exits at about 5x the capital raised. And that number is the basically the same on both sides of the range. Both the upside and downside get slightly better with valuation, but in broad strokes, the returns remain unchanged. From an investor's perspective, whether you are shooting for $200 million or $800 million does not make all that much difference (if you gently forget about capital deployment plans and management fees).

This holds true until you hit the magical $1 billion valuation - this is where things change dramatically. In both the median and the top quartile of outcomes, the previously flat [valuation]/[capital raised] ratio goes up by 50%+. That is means that for each dollar invested there are better returns to limited partners, more carry to the fund, and more fame for the individual investor. So, when you are told that you need to have a shot of being a $1bn+ company, this is probably why.

3) Unicorns are not (necessarily) great for founders

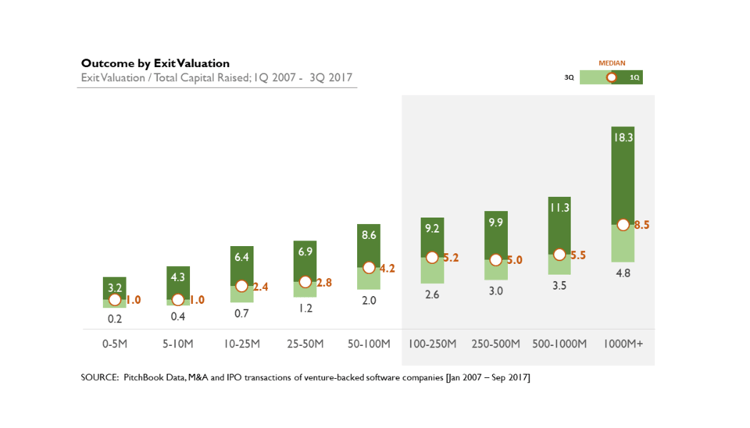

This may be obvious, but if you want to build a big technology company, you will probably need to keep raising (and burning) money. Here's the data:

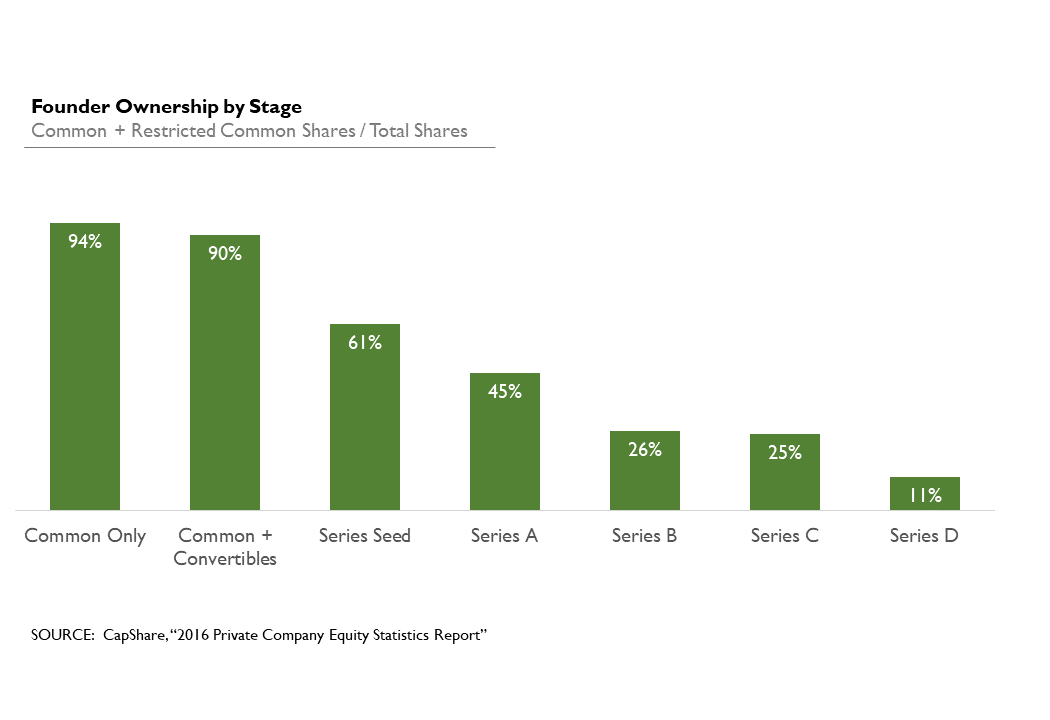

Even if you, as a founder, are a master negotiator, each subsequent round will chip away at your ownership. CapShare did some great work on how that works out in practice - you can find it here. This is how founders fare as their company raises subsequent rounds of equity:

So here is the thing - as a founder, you might not really want that $1 billion valuation. The data paints a plausible and realistic scenario of how you can (more than) double your company's value from a few hundred million to over a billion (with the associated risk, time, stress and gray hair involved), just to find out that you end up making the same amount of money after the dilution.

All of this is just one way to look at the data, but at this point I would guess that it is not the founder's rational self-interest, but rather the (very) lucrative outcome for investors that has generated the current unicorn-or-bust hype. Needless to say, the outsized economic impact of billion-dollar companies and the resulting attention in media and society do not help tamper the narrative.

I can't help but end this with a bit of a rant. Venture capital has a privileged role to fill in advancing innovation that (hopefully) makes us better as a human species. We can (and should) back large, delusional, revolutionary, inspiring, binary outcomes. While Edison Partners does not necessarily operate in this space, I have a deep sense of appreciation (and even friendly envy) for the firms that have funded companies like SpaceX, Coinbase, Udacity, Stemcentrx, and Tesla to question the rationale of existing systems and push us to new limits. But ending up with a narrative in which the only outcomes that matter are the ones over a billion dollars is unfair.

Many (in fact most) successful venture-backed businesses have had an impact on the world, made a name for themselves, and earned a good chunk of change for their founders and employees without coming anywhere near the unicorn valuation mark. There is a lot of value to be created in scaling a business to a couple of hundred million in enterprise value. It is a major feat that requires hard work. It forms the core of the venture economy. It should be recognized, celebrated and promoted.